Top 5 Issues to Consider at the Intersection of Behavioral Health and Public Health (2020 Update)

- By: Christopher Kinabrew, MPH, MSW

- Date

NNPHI is also committed to enhancing the capacity of chief health strategists working at the intersection of public health and other sectors. This blog update considers some of the many developments since 2017 regarding population level data, workforce, strategy, major legislation, and funding. While many federal agencies are relevant to this intersection of public health and behavioral health, this update emphasizes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Public health crises over the past few years, including the opioid and suicide epidemics and COVID-19, have presented increased opportunities for collaboration. Given public health’s commitment to using data to drive decision making, we start with population level data.

5: Population Level Data

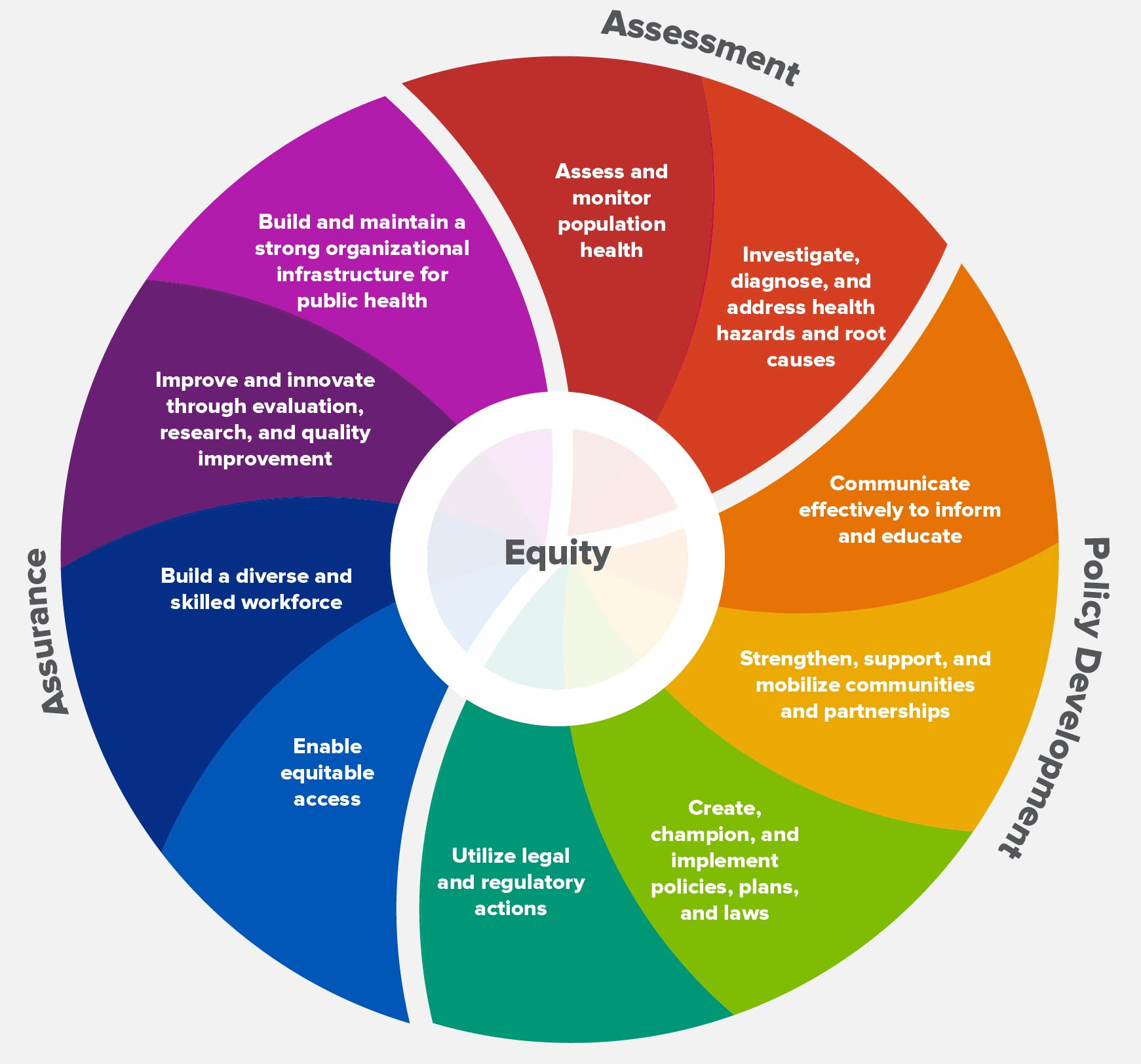

Using the 2020 revised framework, the first Essential Public Health Service is to “assess and monitor population health status, factors that influence health, and community needs and assets.” SAMHSA released the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health providing estimates of substance use and mental illness at the national, state, and substate levels. Highlights included year-over-year rising rates of serious mental illness in adults aged 18-49 years old and major depression in all age groups with increased suicidality, with incremental progress on the opioid epidemic (note: this is pre-COVID data).

CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) released 2019 National Health Interview Survey data briefs on topics including depression, anxiety, and mental health treatment for children. CDC/NCHS has also partnered with the US Census Bureau and other federal agencies to launch the Household Pulse Survey to gauge the impact of the pandemic on employment, spending, food security, housing, education, and dimensions of physical and mental wellness. NCHS published Pulse survey results regarding anxiety and depression here and differences between the earlier NHIS data and Pulse results from Summer 2020 are available here. These reports, as well as a recent MMWR report, highlight considerably elevated mental health conditions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the MMWR, “Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers, and unpaid adult caregivers reported having experienced disproportionately worse mental health outcomes, increased substance use, and elevated suicidal ideation.” Behavioral health fallout from the pandemic will likely be seen for the near future, as noted in this May USA Today interview with Dr. Elinore McCance-Katz, HHS’ first Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Abuse.

Given the increasing burden of behavioral health problems despite the existence of effective interventions, these authors urge public health organizations to enhance and improve behavioral health surveillance. They provide a revised surveillance evaluation framework to support ongoing improvements to behavioral health surveillance systems and ensure their continued usefulness for detecting, preventing, and managing behavioral health problems. At least two states have used methods like CASPER to provide rapids needs assessments of COVID-related issues, opening the door for more extensive and long-lasting surveillance methods. There have been innovative partnerships to collect data in light of COVID-19, yet it remains to be determined how and whether these inter-agency efforts will continue after the pandemic.

4: Workforce

The eighth Essential Public Health Service is to “build and support a diverse and skilled workforce.” The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has been conducting analyses of the adult and pediatric mental health and substance abuse disorder workforce, per the mandate of the 21st Century Cures Act. Recent reports project an undersupply in two of the nine behavioral health occupations they analyze— psychiatrists and addiction counselors. These projections may change based on increased demand and changes in workforce supply related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Trust for America’s Health estimates that over the past decade, the public health workforce has shrunk by approximately 56,000 positions—primarily due to funding issues. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ (ASTHO) most recent profile data suggests “declining budgets and reduced workforce: these characterize state and territorial public health agencies the year before COVID-19.” At the local level, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) reports the estimated number of local health department employees has decreased from 184,000 in 2008 to 153,000 in 2019—a decrease of 17%. Recent funding increases (see #1 below) may be fueling a temporary bump in public health positions related to pandemic response (e.g., contact tracing, testing, etc.), but some of these positions may be only short-lived.

The Trust for America’s Health estimates that over the past decade, the public health workforce has shrunk by approximately 56,000 positions—primarily due to funding issues. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials’ (ASTHO) most recent profile data suggests “declining budgets and reduced workforce: these characterize state and territorial public health agencies the year before COVID-19.” At the local level, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) reports the estimated number of local health department employees has decreased from 184,000 in 2008 to 153,000 in 2019—a decrease of 17%. Recent funding increases (see #1 below) may be fueling a temporary bump in public health positions related to pandemic response (e.g., contact tracing, testing, etc.), but some of these positions may be only short-lived.

At the state and local levels, the Council on State and Territorial Epidemiology’s (CSTE) most recent Epidemiology Capacity Assessment (“2017 ECA”) and data from a local pilot with 27 members of the Big Cities Health Coalition (BCHC) provide detailed insight into positions very relevant to this intersection of public health and behavioral health. The 2017 ECA enumerated 59 state substance abuse epidemiologists but noted an additional 64 were identified as needed to achieve full capacity. Furthermore, there were only 4 mental health epidemiologists enumerated at the state level and 42 more (1058% increase) needed to achieve full capacity. Among the BCHC agencies, 40 substance abuse and 34 mental health epidemiologists were enumerated, while an additional 20 and 15 are needed to achieve ideal capacity, respectively. In 2017, 49% of states had an epidemiology program area lead for Substance Abuse, an increase from 2013 at only 16%. At state health departments, the presence of a lead epidemiologist in Mental Health increased from 2% in 2013 to 14% in 2017. CSTE is currently planning a 2021 ECA, with analysis and final reports likely available in early 2022.

At the local level, the 2019 NACCHO profile estimates approximately 6,700 behavioral health staff working in local health departments (about 6% of the overall local health department workforce). It is notable this represents a significant increase from estimates of 3,700 behavioral health staff in the 2013 and 2016 data. But the number of behavioral health staff had dipped from 2008 by about half and then came back up in 2019. According to 2019 data, a typical staffing pattern for a local health department including behavioral health staff only begins for jurisdictions serving populations of 500,000 or more. Limited or no behavioral health staff in smaller jurisdictions could make cross-agency collaboration and referrals more challenging.

3: Strategy Programs

The fourth and seventh Essential Public Health Services are to “strengthen, support, and mobilize communities and partnerships to improve health” and “assure an effective system that enables equitable access to the individual services and care needed to be healthy.” SAMHSA has historically focused on treatment and recovery while CDC has focused on surveillance, programming, and prevention. While it is challenging to point to an overarching strategy for enhancing mental health surveillance and increasing public health and behavioral health collaboration, there are examples across federal agency plans and frameworks. The HHS Strategic Plan (2018-2022) includes Strategic Objective 2.3, which focuses on reducing the impact of mental and substance use disorders through prevention, early intervention, treatment, and recovery support.

In August, HHS released Healthy People 2030 which includes many relevant objectives, such as MHMD-07, “increas[ing] the proportion of persons with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health disorders who receive treatment for both disorders.” That measure includes a baseline indicating that only 3.4% of adults over age 18 with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health disorders received both mental health care and specialty substance use treatment in 2018.

SAMHSA’s Strategic Plan for 2019-2023 includes an objective related to strengthening public health surveillance that is very focused on the opioid epidemic. While the overarching CDC Strategic Framework is less specific regarding this intersection, CDC has shown increased coordination and collaboration with SAMHSA at the program level on topics including but not limited to opioid overdose prevention, suicide prevention, and tobacco prevention and control, among other priorities. CDC has ramped up its opioid overdose work significantly in the past several years, and recently combined several programs into the Overdose Data to Action cooperative agreement. In the last appropriations cycle, CDC received new funding for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), suicide prevention, gun violence prevention, and administration of the Drug Free Communities program (previously administered by SAMHSA). The SAMHSA representative for the Interagency Committee on Smoking and Health has published a compelling article regarding smoking cessation and improvement of behavioral health conditions.

Implementing strategy and programs at this intersection requires capacity. The above-referenced CSTE ECA measures Essential Public Health Services Capacity. Mental health had the second lowest program area capacity with 90% of states reporting minimal to no capacity (<25%). Less than 85% of states indicated they have partial or less capacity (<50%) in the area of substance abuse. Mental health (94%) and substance abuse (93%) were the most frequently cited areas for needed improvement. The area of substance abuse was rated the highest priority for improving capacity by 63% of states. Among BCHC jurisdictions, 85% indicated a need for improvement in the area of substance abuse and 89% in mental health.

The NACCHO Profile also reports data relevant to local capacity at the intersection of public health and behavioral health, including the proportion of LHDs engaged in assuring access to behavioral healthcare services having increased from 40% in 2010 to 62% in 2019. While that progress is substantial, it also indicated only about 50% of health departments are partnering with mental health and substance abuse providers, or sending data back and forth (i.e., from health department to providers, and vice versa). Those CSTE and NACCHO data points paint a picture of limited state and local capacity for enhancing behavioral health surveillance, as called forth within #5 above.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had, and will continue to have, a substantial impact on behavioral health organizations and our mental health system. The President recently signed an Executive Order creating a Coronavirus Mental Health Working Group in response to the pandemic. The working group will issue its recommendations in mid to late November. As federal, state, and local agencies revisit overarching strategies and programs in light of the unprecedented disruption caused by the pandemic, they may consider opportunities for improved care coordination to address social determinants of health.

2: Major Legislation

The fifth and sixth Essential Public Health Services are to “create, champion, and implement policies, plans, and laws that impact health” and to “utilize legal and regulatory actions designed to improve and protect the public’s health.” One commentator has noted “much of the observed impact of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) on improved access, financial protection, and treatment stems from the combined impact of it and the Affordable Care Act (ACA).”

Researchers have found significant positive associations with the utilization of mental and substance use disorder outpatient services, a trend which continued over the five-year post-MHPAEA period, underscoring the long-term relationship between this policy change and utilization of behavioral health services. As noted above in #3, there is a long way to go in assuring those with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental health disorders receive both mental health care and specialty substance use treatment. All eyes will be on the Supreme Court’s future ruling on the ACA and whether it results in wholesale regulatory changes or more modest tweaks, and any ancillary impacts on addiction coverage and other issues at the intersection of public health and behavioral health.

In terms of major legislation, some of the many items worth noting are the recent passage of five suicide prevention bills that highlight the complementary roles of both mental health and public health, as well as telehealth policy changes. The recent appropriations highlighted below include major appropriations for public health and behavioral health at the federal, state, and local level, including not just funding but also regulatory actions.

1: Funding

The tenth Essential Public Health Service is to “build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for public health.” Public health and behavioral health continue to be heavily reliant on federal discretionary dollars to fund core elements and functions. Recognizing CDC and SAMHSA provide significant extramural funding to the field, tracking CDC and SAMHSA budget trends provides one window into funding of public health and behavioral health.

The CDC budget trend in 2015-2017 had been relatively flat at $6 to $7 billion, then from 2018 to 2020 varied from $8.3 billion to $7.3 billion to just under $8 billion. Recent substantial additional funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020, the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act of 2020, and the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020 added approximately $12.75 billion related to COVID-19, much of which CDC has deployed to states and communities.

The SAMHSA budget trend in 2015-2017 had been relatively flat at $3.5-3.7 billion, then from 2018 to 2020 it increased from $4.2 billon to just under $6 billion, mostly due to the State Opioid Response Grants. Recent additional funding from the three above-referenced COVID-related Acts of 2020 have added resources to SAMHSA’s budget, approximately $425 million of which has been deployed to states and communities.

The above-referenced budget numbers do not include the CARES Act Provider Relief Fund, which has provided additional funding to reimburse hospitals and other health care entities for health care related-expenses or lost revenues attributable to coronavirus. This increased COVID-19 funding to states and communities may present some opportunities for improving public health and behavioral health collaboration. But in the fog of the pandemic and with immediate needs paramount, it is challenging for chief health strategists to fulfill Essential Public Health Service #10 with these COVID-19 funding streams. There is also palpable concern across the field of public health at state and local level regarding future funding stability. Many state and governments are anticipating or experiencing budget shortfalls due to the pandemic and other economic factors.

Conclusions

President John F. Kennedy was quoted as saying, “When written in Chinese, the word crisis is composed of two characters—one represents danger, and the other represents opportunity.” 2020 has certainly been a year of crisis and danger with a near constant spotlight on public health and behavioral health. Those on the frontlines are risking their lives and those serving in leadership roles are under increased pressure.

Having examined the intersection of public health and behavioral health through the lens of population level data, workforce, strategy, major legislation, and funding, below are five recommendations for chief health strategists working at the nexus of public health and behavioral health:

- Do everything possible to address the mental health crisis at hand. “Supporting a Nation in Crisis: Solutions for Local Leaders to Improve Mental Health and Well-Being During and Post-COVID-19” provides practical steps that policymakers and other local leaders can take to improve their communities’ mental health and well-being in both the immediate response to COVID-19 and the long-term recovery phase. Many of the report’s recommendations are low-cost or revenue-neutral.

- Even in the fog of the pandemic, consider opportunities to improve collaboration across public health and behavioral health, especially related to the social determinants of health. When ASTHO convened state leaders in late 2018 to discuss collaboration across public health and behavioral health, key lessons learned centered on the need for shared definitions; addressing the social determinants of health and upstream factors for behavioral health issues; and building the financing and data infrastructure to support behavioral health integration. As public health and behavioral health implement programs and initiatives with COVID-19 supplemental funding, chief health strategists should consider these lessons learned.

- Continue efforts to build capacity within the epidemiology workforce, especially in-state program areas related to mental health and substance misuse. While those are not the only positions relevant to this intersection, chief health strategists may consider them essential positions for improving behavioral health surveillance.

- Consider more explicit references to public health and behavioral health collaboration in future strategic plans. As noted above, there has been increasing public health and behavioral health collaboration in program areas including opioid overdose prevention, suicide prevention, etc. Chief health strategists at the federal, state, territorial, and local levels have opportunities to formalize this collaboration beyond a single program.

- Don’t forget about health equity. The picture is not year clear how increased collaboration at this intersection of public health and behavioral health will help achieve health equity. The overarching movement for mental health parity has been framed in terms of health equity. With the recent release of the 10 Essential Public Health Services, chief health strategists will be considering health equity at the core of this framework and increasing focus on equitable access to individual services and care needed to be healthy (Essential Service #7). Please stay tuned for additional thoughts for achieving health equity through increased collaboration across public health and behavioral health.

Subscribe To Our Communications

Subscribe To Our Communications