Strength in Numbers: My Reflections on the Recent Death Certificate Training in Puerto Rico

- By: awprobot

- Date

At the National Network of Public Health Institutes, I support the Hurricane Response Hub and the five Hurricane Response Hub Technical Assistance Centers. I was given the opportunity to travel to San Juan, Puerto Rico in October to participate in the Puerto Rico Hurricane Response Hub Technical Assistance Center’s Death Certificate Technical Training.

At the National Network of Public Health Institutes, I support the Hurricane Response Hub and the five Hurricane Response Hub Technical Assistance Centers. I was given the opportunity to travel to San Juan, Puerto Rico in October to participate in the Puerto Rico Hurricane Response Hub Technical Assistance Center’s Death Certificate Technical Training.

Two months prior to this trip, I knew little about the death certificate process and was surprised to learn this was the first time physicians, representatives from the Puerto Rico Medical Licensing Board, medical schools, funeral homes, Puerto Rico Department of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention convened to discuss the issues surrounding the inconsistencies in disaster-related death reporting. I believe in public health because of the multidisciplinary approach to tackling health issues, and this training was a prime example of that approach—an exciting and a collaborative process across disciplines and agencies to address the inconsistencies in how disaster-related deaths are recorded.

According to the Sub-Secretary of Health, Dr. Concepción Quiñones De Longo, the purpose of the training was to identify causes of death to fund both future research and future disaster recovery. During the training Dr. De Longo noted, “Attributing deaths to disasters must become part of the doctor’s work culture, integrated into medical school curriculum, and added to continuing education requirements.” She shared that most doctors learn how to fill out a death certificate after their patient has died, and the nurse is the one who usually teaches them how. This event was the first attempt to standardize the training medical professionals receive, which has a lot of potential impacts for both the public health system and medical professional training.

In September 2017, Puerto Rico was hit by Category 4 storm Hurricane Maria1, a storm that left the island without power, clean water, food, and ultimately $90 billion in damages. Five months after the storm, one-fourth of the island still lacked access to electricity, and people were still dying. With a 45 percent increase in mortality, emergency services, hospitals, and morgues were over capacity. Seventy-seven percent of these excess deaths were older adults, and 18 percent came from regions with low socioeconomic development.2

During my time in Puerto Rico, I connected with colleagues and learned more about the controversy surrounding this issue. The official death count from Hurricane Maria is still only 56 deaths. In 2018, the Puerto Rican government commissioned a study from the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health. Researchers estimated an excess of 2,975 deaths in Puerto Rico due to Hurricane Maria between September 2017 and February 2018.22 Following the study publication, Puerto Rican officials did not mandate any updates or changes to the field death certificates submitted between these months.

Inaccuracies in the number of deaths from disasters can have many downstream effects, such as a lack of federal funding during the emergency response, recovery phase, and even funding for planning for future disasters. Without accurate reporting, trends in morbidity and mortality cannot be analyzed and appropriate response during a disaster does not happen. Additionally, families of the deceased are faced with issues related to life insurance policies, collecting social security, and other death-related benefits.

Inaccuracies in the number of deaths from disasters can have many downstream effects, such as a lack of federal funding during the emergency response, recovery phase, and even funding for planning for future disasters. Without accurate reporting, trends in morbidity and mortality cannot be analyzed and appropriate response during a disaster does not happen. Additionally, families of the deceased are faced with issues related to life insurance policies, collecting social security, and other death-related benefits.

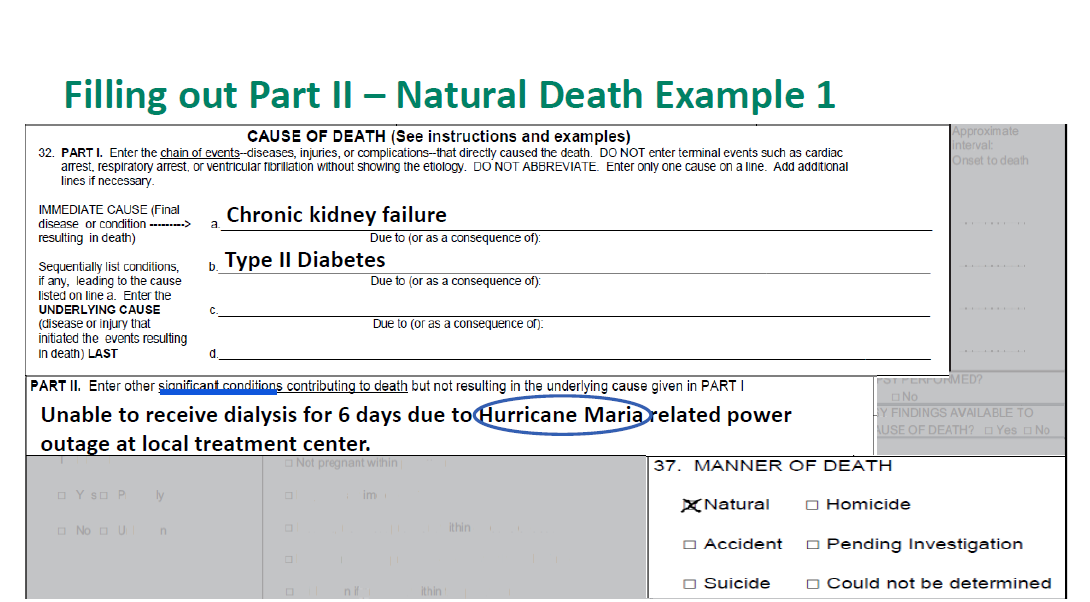

Some of the issues arise when death certifiers complete the section that asks for the direct and indirect causes of death. Direct causes of death following a disaster include smoke inhalation, burns, drowning, hypo/hyperthermia, to list a few. Indirect causes of death are less evident. These can include returning to an unsafe structure, loss of public services, loss or interruption of transportation services, usage of unsafe temporary shelters, evacuation, and electrical accidents—all things that occur because of the disaster. The indirect causes of death may occur weeks or months following the storm, making it challenging for the death certifier to attribute it to the disaster.

“Pero…sin el desastre se hubiesen muerto en el mismo tiempo?” – Without the disaster, would these deaths have happened?

As we continue to work in this space, it’s important to understand that this is not only an issue Puerto Rico faces. Many people in California are exposed to fine particulates due to wildfires. Particulate matter can lead to several negative health effects, such as exacerbated asthma attacks, heart attacks, and strokes. Since the Camp and Woodley fires, there have been 88 recorded deaths attributed to these disasters.3 However, many more people have been impacted by the poor air quality, which may lead to other premature deaths.

Much of the US will continue to struggle with this issue, as well. California will experience more devastating wildfires; the Northeast will see rises in temperatures and increases in heat-related deaths; Florida will see more hurricanes and sea-level rises; the Midwest will face higher temperatures and decreases in crop yields; Washington will deal with increases in flooding and landslides; Alaska’s permafrost will continue to melt; and Hawaii’s fresh water sources will slowly shrink. Accurately capturing any deaths related to these and other disasters is important for public health to respond and prevent future deaths.

This was my first trip to Puerto Rico, the small island in the Caribbean that has been impacted by hurricanes for centuries. My Puerto Rican colleagues showed me what resilience means and how important community, solidarity, and synergy are. Puerto Rico is setting an example for the rest of the country in disaster-related mortality surveillance. This truly is a public health issue that can only be solved with a multidisciplinary approach.

I believe the training’s greatest accomplishment was when the Dean of the medical school, health department representatives, nursing school representatives, examiners board, and funeral directors all agreed to have a Memorandum of Understanding across the institutions as a written commitment to train doctors, students, residents, and nurses to accurately attribute deaths to disasters. Dr. De Longo emphasized how this collective agreement gives more credence to this project. When public health professionals come together across disciplines and livelihoods, they are ready to work and come up with solutions.

Isabella Kaser is a program associate at the National Network of Public Health Institutes where she supports the Hurricane Response Hub, which is part of the National Coordinating Center for Public Health Training.

- 1https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL152017_Maria.pdf

- 2https://publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/downloads/projects/PRstudy/Acertainment%20of%20the%20Estimated%20Excess%20Mortality%20from%20Hurricane%20Maria%20in%20Puerto%20Rico.pdf

- 3https://www.motherjones.com/environment/2019/10/wildfires-are-making-californias-bad-air-quality-even-worse-and-its-killing-people/

Subscribe To Our Communications

Subscribe To Our Communications