Leading the Public Health Workforce

- By: Lisa Tobe, MPH, MFA and Lauren Milliken, MSW, MPH

- Date

A New Hope

The COVID-19 Pandemic revealed a fragile public health infrastructure, bringing extraordinary challenges to an already stretched workforce. Health departments are often under-sourced and understaffed, forcing staff to use antiquated systems, which makes meeting community health needs difficult. Hundreds of public health workers, including those in leadership positions, have left the field or changed jobs due to burnout, low pay, political turmoil, and other understandable reasons since the pandemic began. This version of public health’s “Great Resignation” has only exacerbated a long-standing trend of public workforce resignation.

However, there is renewed hope in the field of public health due to significant federal investment to fortify the nation’s public health infrastructure. During this time of renewal and recommitment, leadership training will play a critical role in developing the current and future public health workforce.

In a concerted effort to focus on leadership and systems thinking skills, three of the ten Public Health Training Centers (Regions IV, VII, and X) established Leadership Institutes (LI) prior to the pandemic to address these contemporary leadership training needs. The PHTC network, composed of ten regionally-based PHTCs funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), offers significant public health workforce development—from supporting students in increasing public health knowledge to training senior-level staff in health equity. The first of these LIs, the Northwest Public Health & Primary Care Leadership Institute, was established by the University of Washington’s Northwest Public Health Training Center in 2003 to serve Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. This leadership institute specifically supports mid-level career professionals from public health and community-based primary care settings to develop equitable and practical approaches to population health.

The Great Plains Leadership Institute (GPLI) began in 2005 as an initiative of the Nebraska Educational Alliance for Public Health Impact (NEAPHI). Current sponsors include the Midwestern Public Health Training Center, the University of Nebraska Medical Center – College of Public Health, and the Nebraska Health and Human Services System. The institute’s year-long competency-based training program is for senior and emerging leaders looking to improve the health and well-being of populations and communities in Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas. The training includes mentoring and coaching and collaborative practice projects.

The Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute is the newest of the PHTC’s previously established leadership institutes. The leadership institute within Region IV PHTC at Emory University began running a public health leadership institute in the fall of 2019, just before the pandemic started. Region IV’s leadership institute provides training for emerging leaders who work in state, local, and tribal public health departments/tribal health organizations or Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) and FQHC Look-Alikes in the eight states that comprise Region IV (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee)—serving the most expansive area of all PHTCs.

Although each of these LIs is unique in its design, all three have similar application processes, a medium-sized cohort (between 24 and 36 participants), and a focus on leadership at the program management and supervisory level. All three of these LIs also have a similar mission: to increase health equity by equipping emerging leaders with extensive training. As the field experiences a sharp decline in the numbers of state and local public health professionals in practice, these PHTC LIs empower emerging leaders to stay in the field and continue in the workforce by creating strong networks of peers, encouraging professional development, and delivering a robust curriculum.

| Public Health Training Center* | Associated Leadership Institute | State Area | Established | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region IV Public Health Training Center | Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute | Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee | 2019 for professionals at PH departments; expanded in 2022 to include professionals at FQHCs/FQHC Look-Alikes | Free |

| Midwestern Public Health Training Center (Region VII) | Great Plains Leadership Institute | Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas | 2005 (with major revisions to curriculum and competencies in 2015-2016 | Fee-based (with available scholarships)** |

| Northwest Public Health Training Center (Region X) | Northwest Public Health & Primary Care Leadership Institute | Alaska. Idaho, Oregon, and Washington | 2003; (with major revisions in 2015 and 2019) | Fee-based (with available scholarships)** |

| *PHTCs are supported by the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) ** See current applications for costs |

||||

Spotlight: Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute

Melissa (Moose) Alperin, EdD, MPH, MCHES, principal investigator and project director of the Region IV PHTC, considers her LI a “newcomer” compared to the two leadership institutes offered by Regions VII and X PHTCs. While Region IV’s LI is only in its fourth cohort, its leadership program is comprehensive and thoughtful, serving leaders representing one-fifth of the nation’s population. “When we set our [LI] up, we were very intentional about the ideal components. We wanted representation from every state,” said Alperin. “Additionally, we wanted slots for individuals that work in tribal health departments and tribal health organizations.” Region IV’s LI development team was also intentional about eliminating financial barriers to participation when it became the first completely free LI program, including travel coverage as needed.

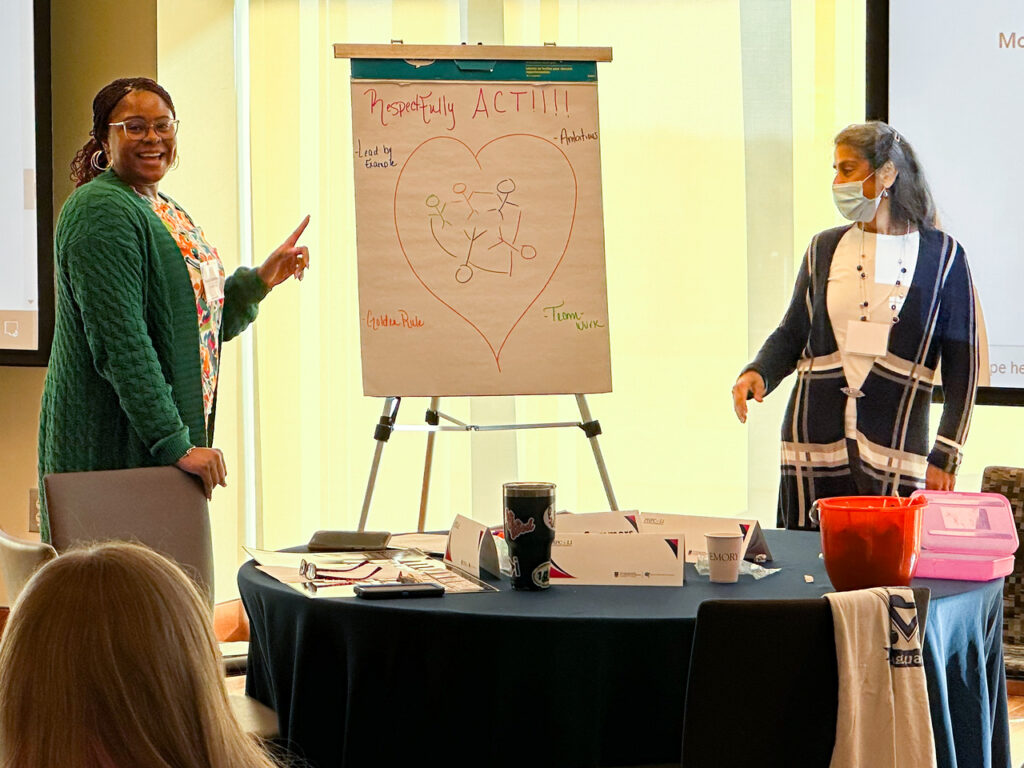

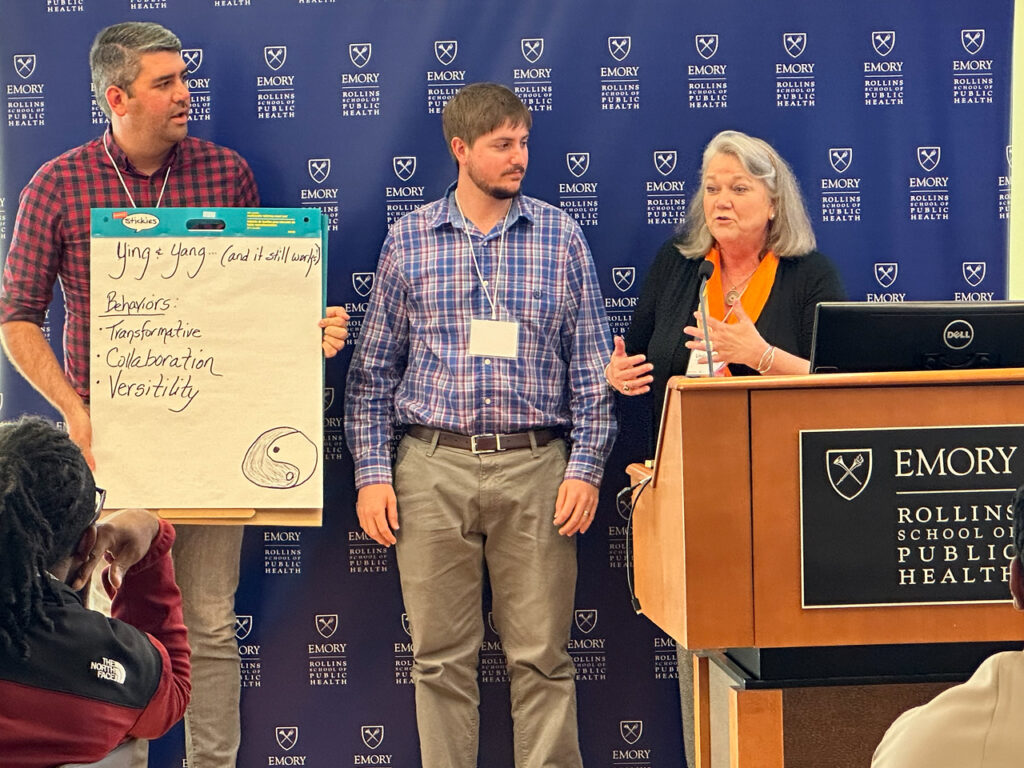

Using a health equity lens, the overall learning objectives for the Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute are to identify personal leadership strengths, address a leadership challenge through a self-directed adaptive approach, engage in peer consulting with regional colleagues, and apply leadership competencies. Alperin acknowledges the work done to meet these competencies is not done in a silo and emphasizes the importance of partnering with other public health and leadership organizations to move the work forward. Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute staff worked closely with content experts and partners at the J.W. Fanning Institute for Leadership Development, located at the University of Georgia. The J.W. Fanning Institute facilitates the program, including an orientation, an opening retreat, six virtual sessions, self-assessments, on-demand webinars, and readings.

Using a health equity lens, the overall learning objectives for the Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute are to identify personal leadership strengths, address a leadership challenge through a self-directed adaptive approach, engage in peer consulting with regional colleagues, and apply leadership competencies. Alperin acknowledges the work done to meet these competencies is not done in a silo and emphasizes the importance of partnering with other public health and leadership organizations to move the work forward. Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute staff worked closely with content experts and partners at the J.W. Fanning Institute for Leadership Development, located at the University of Georgia. The J.W. Fanning Institute facilitates the program, including an orientation, an opening retreat, six virtual sessions, self-assessments, on-demand webinars, and readings.

At the heart of each eight-month-long R-IV LI program is adaptive leadership, a concept introduced by Heifetz and colleagues in 2009.[i] Adaptive leadership emphasizes alternative perspectives, pushes practitioners to move beyond traditional data sets to find answers, and uses collective energy to cultivate wisdom. Adaptive leadership requires fellows to lean into complex or new challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic gave fellows several opportunities to put adaptive leadership into practice. Fellows reached out to each other for support as they began working on vaccination and communication plans and strategizing for combating the pandemic.

– Region IV LI participant

Survey responses from Region IV’s LI indicate a strong positive effect. Almost all the survey respondents from the first three cohorts (n=70) agreed or strongly agreed that they had identified their leadership strengths (97.1%), applied leadership competencies in the context of public health (95.7%), and addressed leadership challenges using adaptive leadership skills 92.9%. To amplify these learnings, Region IV developed a six-part podcast series, Adaptive Leadership for Public Health, focusing on creative thinking to address persistent challenges in twenty-minute snapshots.

Throughout the LI sessions, facilitators work to ensure participants gain the skills to address health inequities within their scope of influence using a health equity lens. For instance, participants discuss conflict with an equity lens and, as one of their intersession activities, discuss their results of a cultural intelligence assessment. Another hope for using health equity is to expand what is considered health equity work. Elizabeth Kidwell, MPH, CHES, the training specialist and field placement manager for the Region IV PHTC, said “A specific role might not be stated as health equity-focused, but a health equity lens can hopefully help fellows broaden the idea of what constitutes equity work.” For instance, regardless of job title, a fellow can increase health equity by being conscious about how a community is described, among other typical daily tasks.

The Region IV PHTC leadership wants emerging leaders to believe they may make a difference. “For this audience, one of the things we hope is learned through this process is that they know they have an impact in whatever scope of influence they have,” said Laura Lloyd, MPH, MCHES, Associate Director for the Region IV Public Health Training Center. “Whether that’s addressing disparities in their community, making their organization more inclusive and welcoming, or having a workforce that looks more like them.” Despite being new, the Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute appears to be making a difference in leadership in local, state, and tribal health departments and FQHCs/FQHC Look-Alikes.

Increasing Capacity

Soon, the Region IV Public Health and Primary Care Leadership Institute will no longer be the newest LI. As part of the new 2022 funding, HRSA requires all ten Public Health Training Centers to offer leadership institutes that integrate public health with primary care designed to increase health outcomes in the communities within their regions. The remaining PHTCs without a current LI are in various stages of development and implementation for their new leadership programs.

Leadership development for the current and future public health workforce is necessary and urgent. PHTC-based leadership institutes have demonstrated that they can help build and sustain a skilled workforce of public health leaders able to address complex public health challenges. Long-term investment and an increase in the number of public health leadership institutes will make the development of leadership more accessible and possible.

Endnotes:

[i] Heifetz RA, Grashow A, Linsky M. The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and theWorld. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2009.

Subscribe To Our Communications

Subscribe To Our Communications