Beyond Training for Health Equity

- By: Multiple Authors

- Date

People gravitate toward careers in public health research and practice for a reason—to help their communities in concrete and enduring ways.

People gravitate toward careers in public health research and practice for a reason—to help their communities in concrete and enduring ways.

With that strong commitment to “doing good,” we persevere in the face of shrinking funding, lacking resources, sharp-edged politics, and mountainous bureaucracy. The growing and vibrant movement to stem health inequities is a manifestation of our grit and determination in the face of systemic opposition and entrenched social injustice.

How are public health practitioners learning to advance health equity by acting more effectively on the root causes of inequity in the distribution of disease and illness? For more than 16 years, the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) has explored just this question.

NACCHO offers staff of local public health departments resources to raise awareness about and address health inequities and social injustice in cities and counties across the United States. These resources include Roots of Health Inequity, an educational website that raises questions about the root causes of health inequities, shares insights, and provides an online space for discussion.

Elevate caught up with NACCHO’s Senior Director for Health Equity and Social Justice Initiatives, Dr. Richard Hofrichter, to discuss how the organization is engaging its members to advance health equity both rapidly and incrementally.

To address structural barriers to health equity, do we need to redefine or reinterpret the concept of “training” for social justice work?

I don’t think of this work as “training.” The concept of training is limited and makes assumptions about who should be a teacher, who should be a learner, and who should be funneling knowledge to whom. It’s easy to transmit facts from teacher to learner about topics like inspecting a restaurant or calculating the incidence and prevalence of an illness.

It’s much more difficult to “train” people when it comes to addressing issues like structural racism.

Taking cues from Paulo Freire’s work, we should instead encourage dialogue that draws attention to the ways people think about the world around them and everything in it—ways that help to obscure deep social divisions and their causes. According to this point of view, dialogue is a process that happens over a long period of time and involves having honest conversations and being unafraid of feeling uncomfortable.

Engaging in transformative dialogue can shift a person’s consciousness by helping them to come to insights and discover new perspectives they may not have considered before. Through their participation in the process, people end up asking questions about the public’s health that are much different from the ones we’re asking currently.

Different questions can yield more socially just and equitable approaches to public health research, policy, and practice.

What is “public health professionalism” and how does it act as a facilitator and barrier to addressing health inequity?

It’s difficult to address health inequities when identifying as a professional first—an expert, a technician, a scientist, an administrator—rather than someone situated in a cultural context, who is fully aware of their values and position in a society that privileges some people over others. In this work, you can’t think of yourself as a professional exclusively. By separating ourselves from our own values and beliefs, some of us can fail to recognize the needs of the communities we serve and the knowledge our communities have to offer about lived experiences and the causes and sources of those experiences.

Some might hide behind the ideas of neutrality and objectivity, which is useful in answering certain questions about diseases, their medical treatment, and the ecological environment from which they arise, but it’s much less useful in addressing health inequities. How we explain the world, frame problems, and collect and analyze public health data are all dependent on the culture in which public health professionals work and how our identities as professionals and people interact with this culture.

To work effectively on eliminating health inequity, having self-awareness and understanding of our position and power is critical. I believe people need to bring their whole selves to the work, not simply their professional identities as experts.

There is no neutral place to stand. You’re always standing somewhere, and you can’t claim not to have values or that somehow you’re holding those values at bay. It just is not possible.

We all need to be citizen-professionals.

People in the workforce are at very different places in their understanding of and willingness to address health equity and social injustices. Should we meet them where they are?

Right, that’s a good question. Well, I’m probably one of the few people you’ll find who does not agree with “meeting people where they are,” because what if they’re in a bad place?

I don’t worry about angering or confusing people who disagree with or don’t understand the idea of social justice. This is about engaging people who are interested. Watering down ideas for fear of scaring people off with certain words and phrases—like “social justice” and “racism”—is completely unproductive when it comes to achieving social justice for people who have been systematically excluded and marginalized.

In response to the kind of question you asked, our conservative opponents, by contrast, come out right away and say, “This is where we are and where we want to take you. Do you want to join us? This is where we’re going. This is who we are.” They state the goal, they explain it, and that’s it. People are going to join them or not.

Coded language introduces obstacles to getting at the truth and doing right by our communities. Further, social justice is an idea with roots which, for our purposes, can be traced to the Industrial Revolution. Public health should own that.

NACCHO’s Health Equity and Social Justice Initiatives aim to be provocative. We want to find and engage people—and there are plenty of them—who have the value base and commitment that it takes to do the work, but just need the support and know-how of colleagues across the country.

What gap will be filled by the new Roots of Health Inequity module about the relationship between public narratives and health inequities? How does it align with NACCHO’s health equity framework?

We want to encourage people to consider the ways in which language, imagery, and the stories we tell in public health may be a bit constraining when it comes to working on health inequities. First, the new module will highlight seemingly innocuous statements that are used commonly in the health communications and marketing we’re used to seeing and then encourage discussion about how the framing of issues affects our interpretation of what is actually going on and who is doing what to perpetuate health inequities.

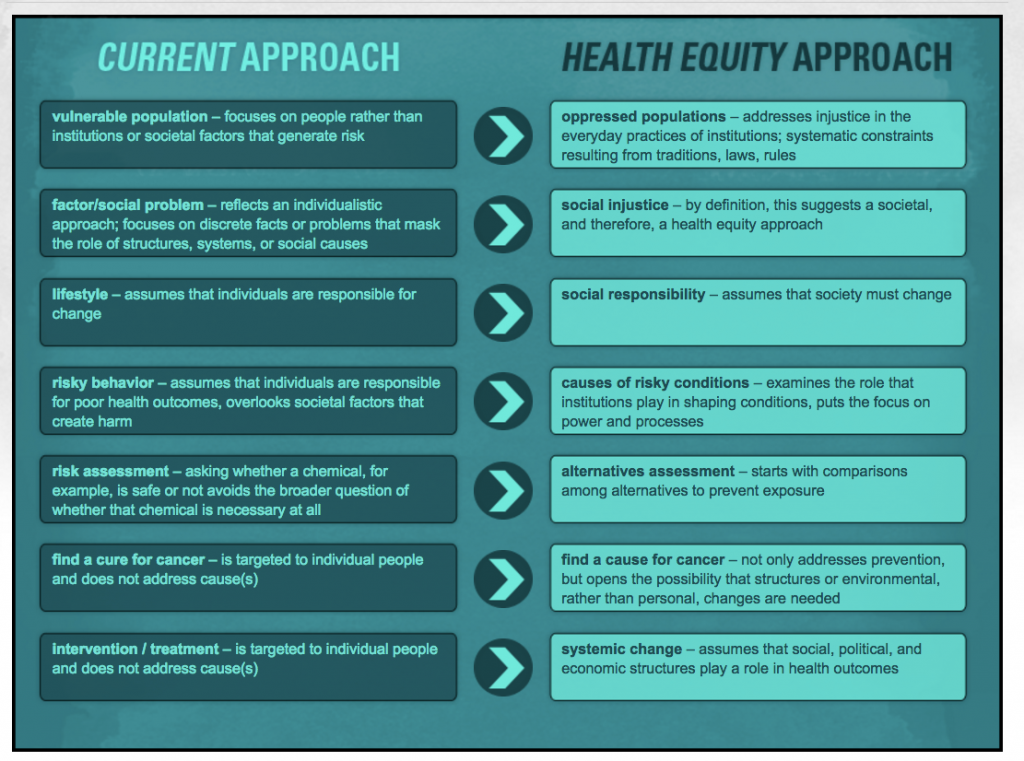

For example, think about the language used in public health publications about “vulnerable populations.” People are made vulnerable. They’re placed under threat. They are not born vulnerable—except children, maybe, but not whole populations. This phrase is condescending, demeaning, and victimizing, and its use encourages a particular perspective on people who have been systematically marginalized. That perspective then impacts the research, policies, and practices we develop as public health professionals.

Click on the image to enlarge. “How Language Choices Affect Meaning” activity from rootsofhealthinequity.org, about how beliefs expressed in language constrain or enable strategies and actions. In this activity, participants match and contrast key phrases in common use among public health professionals working toward health equity and social justice.

Second, we need to explore how building or transforming the public health narrative about health inequities can change how the wider public thinks about why some populations are healthier than others.

Consider the kinds of messages we’re used to seeing in public health promotion and health communications campaigns: Individuals should take responsibility. Eat your vegetables! Eat right to keep fit! Let’s do obesity education! We’re going to teach people to eat right and exercise.

But, are health communications professionals also going to share how agribusiness promotes junk food? Are they also showing people how unhealthy food is put at eye level for children to see and access in supermarkets? Are we going to explore whether our society can really explain away today’s obesity epidemic as people beginning to get stupid and lazy, all at once, 35 years ago?

The new module about public narrative will explore the social and political interests that can offer answers to such questions. These are the kinds of questions we want to encourage our learners to ask, not by cramming facts down their throats, but rather by encouraging them to see—to notice the political ideologies embedded in language, imagery, and stories that avoid confronting injustice. §

Want to advance health equity in your community?

What can you do to advance health equity? Join forces with your local community organizers, and band together with like-minded public health colleagues ready to take action on social injustice. Check out the listserv, Spiritof1848, the social justice caucus of the American Public Health Association.

Want to learn more about the root causes of health inequities?

Explore some of the literature below and connect with NACCHO’s online Roots of Health Inequity course.

About Health Inequity

Krieger, N. (2011). Epidemiology and the people’s health: Theory and context. New York: Oxford University Press.

NACCHO. (2014, May). “Expanding the Boundaries Health Equity and Public Health Practice.”

NACCHO. (2014, May). “Exploring the Roots of Health Inequity: Essays for Reflection.”

NACCHO. (2016, May). “Health Equity: A Charge for Public Health.”

Nathanson, C. A. (2007). Disease prevention as social change: The state, society, and public health in the United States, France, Great Britain, and Canada. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Roberts, S. (2009). Infectious fear: Politics, disease, and the health effects of segregation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Schulz, A. J., & Mullings, L. (2006). Gender, race, class, and health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Scott-Samuel, A., & Smith, K. E. (2015). Fantasy paradigms of health inequalities: Utopian thinking? Social Theory & Health, vol 15: 1-19.

Schrecker, T., & Bambra, C. (2015). How Politics Makes Us Sick: Neoliberal Epidemics (London: Palgrave-MacMillan).

Critical Pedagogy and Critical Race Theory

Resources to help anyone lay a foundation for anti-racist practice in all aspects of public health work.

Ayers, W., Hunt, J. A., & Quinn, T. (1998). Teaching for social justice: A democracy and education reader. New York: New Press.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2013). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (4th ed.). New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

Haney-López, I. (2014). Dog whistle politics: How coded racial appeals have reinvented racism and wrecked the middle class. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hill, J. H. (2008). The everyday language of white racism. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell.

Authors:

Richard Hofrichter, PhD, Senior Director, Health Equity and Social Justice Initiatives at the National Association of County and City Health Officials.

Mikhaila Richards, MS, Communications Strategist at the National Coordinating Center for Public Health Training at NNPHI.

Subscribe To Our Communications

Subscribe To Our Communications